Consulting

Over the years management consultants around the world receive more than $5 billion for their services. Much of this money pays for impractical data and poorly implemented recommendations. It is the objective of AEDF to reduce this waste for our clients at all levels of the consulting assignment.

AEDF has developed a more effective consulting approach that comes from the growing frustrations of many clients who have not received effective consulting. Our consulting method stems from our experience supervising beginning consultants and from the many conversations and associations we have had with consultants and clients in our field of work worldwide. These experiences allow AEDF to take a more holistic approach in addressing and clarifying our client’s needs. When clarity about purpose exists, both parties are more likely to handle the engagement process satisfactorily.

A Hierarchy of Purposes

We at AEDF manage and consult on a broad range of activities for many firms and their clients. AEDF categorizes activities in terms of our professional’s area of expertise in competitive analysis, corporate strategy, operations management, and our client’s needs.

AEDF also approaches the consulting process as a sequence of phases: entry, contracting, diagnosis, data collection, feedback, and implementation. However, these phases are usually less discrete than most consultants may admit. The AEDF process provides answers to the following questions:

Why is a conceptual framework of objectives important in decision making?

What are the most important characteristics of good objectives?

How should objectives be chosen and established?

How can objectives be used profitably by management?

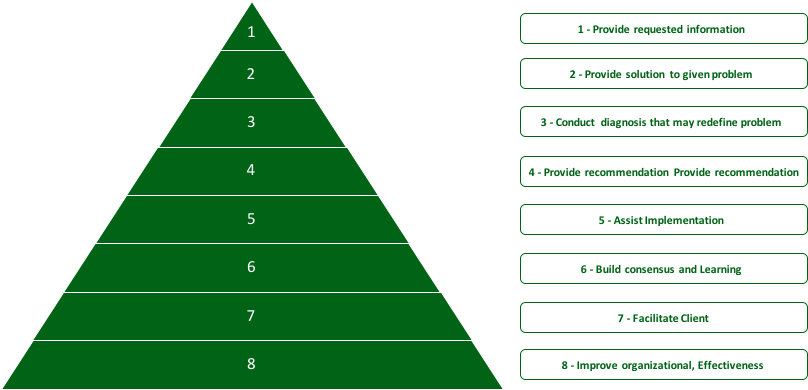

Exhibit A below outlines the sequencing or hierarchy of our consulting process.

Exhibit A hierarchy of consulting purposes

1.

Providing Information

Perhaps the most common reason for seeking assistance is to obtain information. Compiling that information may involve attitude surveys, cost studies, feasibility studies, market surveys, or analyses of the competitive structure of an industry or business. The client may want a consultant’s special expertise or more accurate up-to-date information the firm cannot provide. Or the client may be unable to spare the time and resources to develop the data internally. Often, information is all a client wants. But the information a client needs sometimes differs from what the consultant is asked to furnish. Seemingly impertinent questions from both sides should not be cause for offense—they can be highly productive in providing requested information. Moreover, professionals have a responsibility to explore the underlying needs of their clients.

2. Solving Problems

Managers often give consultants difficult problems to solve. For example, a client might wish to know whether to make or buy a component, acquire, or divest a line of business or change a marketing strategy.

Seeking solutions to problems of this sort is certainly a legitimate function. But the consultant also has a professional responsibility to ask whether the problem as posed is what most needs solving. Very often the client needs help most in defining the real issue.

A management consultant should neither reject nor accept the client’s initial description too readily. If a problem is presented as low morale and poor performance in the hourly work force, the consultant who buys this determination on faith might spend a lot of time studying symptoms without ever uncovering causes. On the other hand, a consultant who too quickly rejects this way of describing the problem will end a potentially useful consulting process before it begins.

3. Effective Diagnosis

Much of management consultants’ values lie in their expertise as diagnosticians. Nevertheless, the process by which an accurate diagnosis is formed sometimes strains the consultant-client relationship, since managers are often fearful of uncovering difficult situations for which they might be blamed.

Although the need for independent diagnosis is often cited as a reason for using outsiders, drawing members of the client organization into the diagnostic process makes good sense.

4. Recommending Actions

The engagement characteristically concludes with a written report or oral presentation that summarizes what the consultant has learned and that recommends in some detail what the client should do. Firms devote a great deal of effort in designing their reports so that the information and analysis are clearly presented, and the recommendations are convincingly related to the diagnosis on which they are based. Many people would probably say that the purpose of the engagement is fulfilled when the professional presents a consistent, logical action plan of steps designed to improve the diagnosed problem. The consultant recommends, and the client decides whether and how to implement.

For example, a nationalized public utility in a developing country struggled for years to improve efficiency through tighter financial control of decentralized operations. This sort of thing happens more often than management consultants like to admit, and not only in developing countries.

And consultants frequently blame clients for not having enough sense to do what is obviously needed. Unfortunately, this thinking may lead the client to look for yet another candidate to play the game with one more time. In the most successful relationships, there is not a rigid distinction between roles; formal recommendations should contain no surprises if the client helps develop them and the consultant is concerned with their implementation.

5. Implementing Changes

The consultant’s proper role in implementation is a matter of considerable debate in the profession. Some argue that one who helps put recommendations into effect takes on the role of manager and thus exceeds consulting’s legitimate bounds. Others believe that those who regard implementation solely as the client’s responsibility lack a professional attitude, since recommendations that are not implemented (or are implemented badly) are a waste of money and time. And just as the client may participate in diagnosis the consultant’s role, so there are many ways in which the consultant may assist in implementation

A consultant will often ask for a second engagement to help install a recommended new system. However, if the process to this point has not been collaborative, the client may reject a request to assist with implementation, simply, because it represents such a sudden shift in the nature of the relationship. Effective work on implementation problems requires a level of trust and cooperation that is developed gradually throughout the engagement.

In any successful engagement, the consultant continually strives to understand which actions, if recommended, are likely to be implemented and where people are prepared to do things differently. Recommendations may be confined to those steps the consultant believes will be implemented well. Some may think such sensitivity amounts to telling a client only what he wants to hear. Indeed, a frequent dilemma for experienced consultants is whether they should recommend what they know is right or what they know will be accepted. But if the assignment’s goals include building commitment, encouraging learning, and developing organizational effectiveness, there is little point in recommending actions that will not be taken.